I hacked up a thing this weekend for sharding the blocks database for large setups. Basically, when the number of blocks in the folder database exceeds a threshold, two new databases are created and blocks are written to those instead. When they reach the same size threshold, four new databases are created, and so on, doubling at each level.

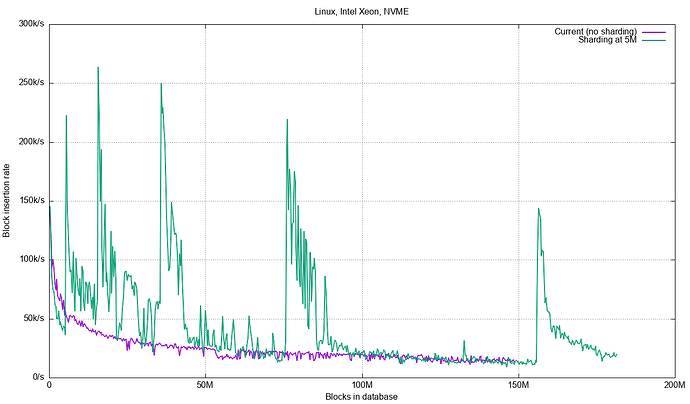

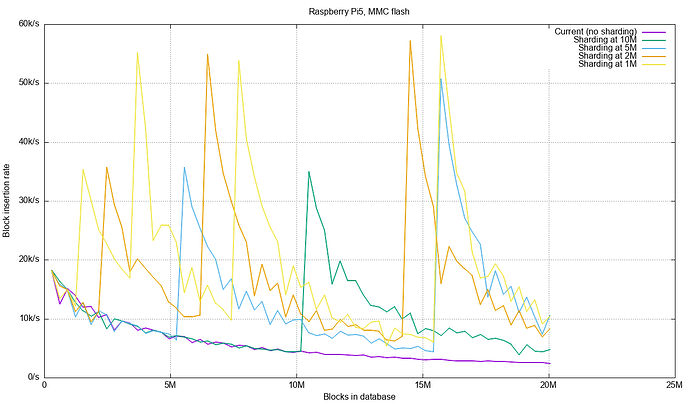

The precise level at which it’s optimal to switch up to the next level depends on the system performance. I’ve run benchmarks on my middle-of-the-road Intel server with NVME storage and my Raspberry Pi 5 with MMC storage and, unsurprisingly, they are quite different. Nevertheless, they both get significantly improved performance from sharding.

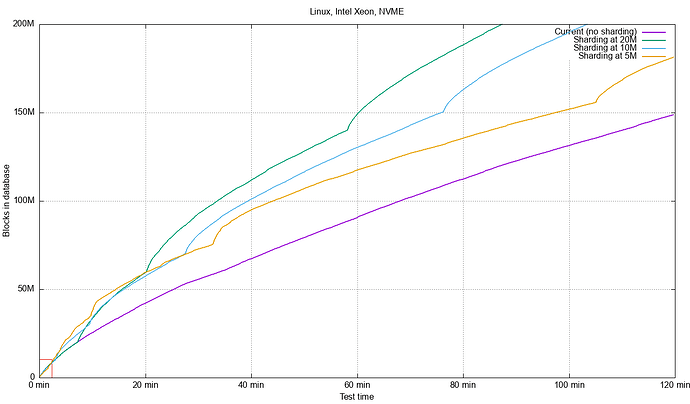

Here are a number of benchmark runs on my Intel server. The benchmark simulates inserting large files (1234 blocks each) in batches of 250 until we reach 200 million blocks or a maximum time of two hours. 200M blocks is about 24 TiB of data assuming the smallest block size.

The test does not reach 200 M blocks with the current code, stopping at 150 M blocks after two hours. With sharding at 5M, 10M and 20M blocks we see increased performance. In this case, 20M blocks per database turns out to be best, due to the increased overhead of doing inserts into 64, 128, etc databases. The code does concurrent inserts/commits to several databases up to the limit of the number of CPU cores in the system. This means we get nice gains when writing to 2, 4, 8 databases, but when we need to write blocks to 128 databases we’re going to be suffering a bit from multiple commit/checkpoint cycles per batch.

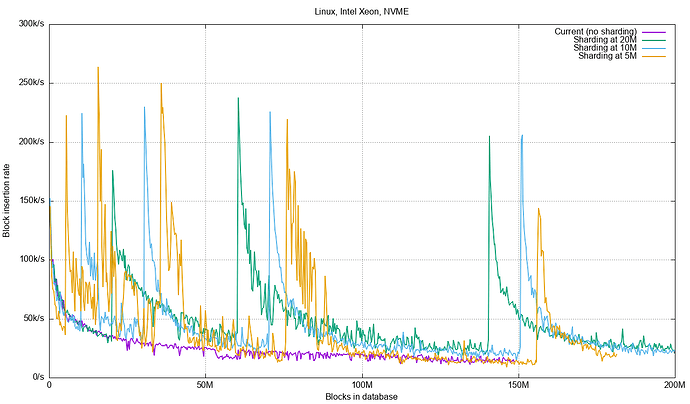

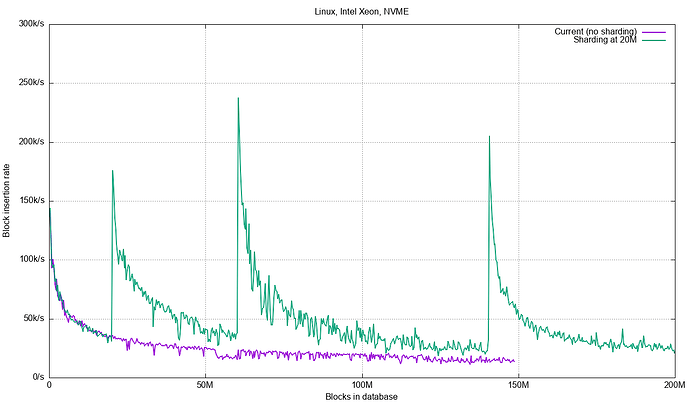

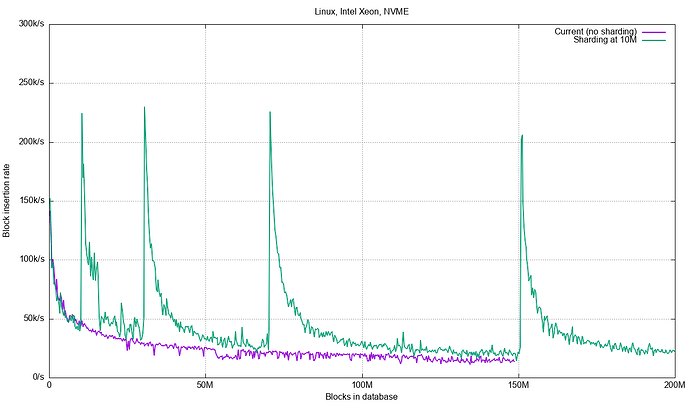

Looking at write performance as a function of the number of blocks in the database, we can see the spikes when new databases are taken on:

The Raspberry has no chance of reaching 200M blocks in reasonable time so the benchmark tries for 20M blocks instead:

Here the smallest sharding threshold at 1M blocks turns out to be most efficient, indicating that this will need to be a user tunable thing.

That all said, if you look at the topmost graph again you’ll see I highighted a span with a red rectangle in the lower left. That is were 95% of users reside according to usage reporting.

There’s some code at wip: use sharding for block database by calmh · Pull Request #10454 · syncthing/syncthing · GitHub if anyone wants to play with this.